Spock comes with a powerful extension mechanism, which allows to hook into a spec’s lifecycle to enrich or alter its behavior. In this chapter, we will first learn about Spock’s built-in extensions, and then dive into writing custom extensions.

Spock Configuration File

Some extensions can be configured with options in a Spock configuration file. The description for each extension will

mention how it can be configured. All those configurations are in a Groovy file that usually is called

SpockConfig.groovy. Spock first searches for a custom location given in a system property called spock.configuration

which is then used either as classpath location or if not found as file system location if it can be found there,

otherwise the default locations are investigated for a configuration file. Next it searches for the SpockConfig.groovy

in the root of the test execution classpath. If there is also no such file, you can at last have a SpockConfig.groovy

in your Spock user home. This by default is the directory .spock within your home directory, but can be changed using

the system property spock.user.home or if not set the environment property SPOCK_USER_HOME.

Stack Trace Filtering

You can configure Spock whether it should filter stack traces or not by using the configuration file. The default value

is true.

runner {

filterStackTrace false

}Parallel Execution Configuration

runner {

parallel {

//...

}

}See the Parallel Execution section for a detailed description.

Built-In Extensions

Most of Spock’s built-in extensions are annotation-driven. In other words, they are triggered by annotating a

spec class or method with a certain annotation. You can tell such an annotation by its @ExtensionAnnotation

meta-annotation.

Ignore

To temporarily prevent a feature method from getting executed, annotate it with spock.lang.Ignore:

@Ignore

def "my feature"() { ... }For documentation purposes, a reason can be provided:

@Ignore("TODO")

def "my feature"() { ... }To ignore a whole specification, annotate its class:

@Ignore

class MySpec extends Specification { ... }In most execution environments, ignored feature methods and specs will be reported as "skipped".

By default, @Ignore will only affect the annotated specification, by setting inherited to true you can configure it to apply to sub-specifications as well:

@Ignore(inherited = true)

class MySpec extends Specification { ... }

class MySubSpec extends MySpec { ... }Care should be taken when ignoring feature methods in a spec class annotated with spock.lang.Stepwise since

later feature methods may depend on earlier feature methods having executed.

IgnoreRest

To ignore all but a (typically) small subset of methods, annotate the latter with spock.lang.IgnoreRest:

def "I'll be ignored"() { ... }

@IgnoreRest

def "I'll run"() { ... }

def "I'll also be ignored"() { ... }@IgnoreRest is especially handy in execution environments that don’t provide an (easy) way to run a subset of methods.

Care should be taken when ignoring feature methods in a spec class annotated with spock.lang.Stepwise since

later feature methods may depend on earlier feature methods having executed.

IgnoreIf

To ignore a feature method or specification under certain conditions, annotate it with spock.lang.IgnoreIf,

followed by a predicate and an optional reason:

@IgnoreIf({ System.getProperty("os.name").toLowerCase().contains("windows") })

def "I'll run everywhere but on Windows"() {Precondition Context

To make predicates easier to read and write, the following properties are available inside the closure:

sys-

A map of all system properties

env-

A map of all environment variables

os-

Information about the operating system (see

spock.util.environment.OperatingSystem) jvm-

Information about the JVM (see

spock.util.environment.Jvm) shared-

The shared specification instance, only shared fields will have been initialized. If this property is used, then the whole annotated element cannot be skipped up-front without initializing the shared instance.

instance-

The specification instance, if instance fields, shared fields, or instance methods are needed. If this property is used, the whole annotated element cannot be skipped up-front without executing fixtures, data providers and similar. Instead, the whole workflow is followed up to the feature method invocation, where then the closure is checked, and it is decided whether to abort the specific iteration or not.

data-

A map of all the data variables for the current iteration. Similar to

instancethis will run the whole workflow and only skip individual iterations.

Using the os property, the previous example can be rewritten as:

@IgnoreIf({ os.windows })

def "I will run everywhere but on Windows"() {You can also give an optional reason why the given feature or specification is to be ignored:

@IgnoreIf(value = { os.macOs }, reason = "No platform driver available")

def "For the given reason, I will not run on MacOS"() {By default, @IgnoreIf will only affect the annotated specification, by setting inherited to true you can configure it to apply to sub-specifications as well:

@IgnoreIf(value = { jvm.java8Compatible }, inherited = true)

abstract class Foo extends Specification {

}

class Bar extends Foo {

def "I won't run on Java 8 and above"() {

expect: true

}

}If multiple @IgnoreIf annotations are present, they are effectively combined with a logical "or".

The annotated element is skipped if any of the conditions evaluates to true:

@IgnoreIf({ os.windows })

@IgnoreIf({ jvm.java8 })

def "I'll run everywhere but on Windows or anywhere on Java 8"() {Care should be taken when ignoring feature methods in a spec class annotated with spock.lang.Stepwise since

later feature methods may depend on earlier feature methods having executed.

To use IDE support like code completion, you can also use the argument to the closure and have it typed as

org.spockframework.runtime.extension.builtin.PreconditionContext. This enables the IDE with type information

which is not available otherwise:

@IgnoreIf({ PreconditionContext it -> it.os.windows })

def "I will run everywhere but not on Windows"() {Using data.* to filter out iterations is especially helpful when using .combinations() to generate iterations.

@IgnoreIf({ os.windows })

@IgnoreIf({ data.a == 5 && data.b >= 6 })

def "I'll run everywhere but on Windows and only if a != 5 and b < 6"(int a, int b) {

// ...

where:

[a, b] << [(1..10), (1..8)].combinations()

}Also note that the condition is split into separate @IgnoreIf annotations so that they can be evaluated independently.

It is good practice ordering them based on their specificity, so that the least specific one is evaluated first, that is from static to shared to instance.

If you need to combine the conditions in a single @IgnoreIf annotation, you should order them from least specific to most specific inside as well.

Requires

To execute a feature method under certain conditions, annotate it with spock.lang.Requires,

followed by a predicate:

@Requires({ os.windows })

def "I'll only run on Windows"() {Requires works exactly like IgnoreIf, except that the predicate is inverted. In general, it is preferable

to state the conditions under which a method gets executed, rather than the conditions under which it gets ignored.

If multiple @Requires annotations are present, they are effectively combined with a logical "and".

The annotated element is skipped if any of the conditions evaluates to false:

@Requires({ os.windows })

@Requires({ jvm.java8 })

def "I'll run only on Windows with Java 8"() {PendingFeature

To indicate that the feature is not fully implemented yet and should not be reported as error, annotate it with spock.lang.PendingFeature.

The use case is to annotate tests that can not yet run but should already be committed.

The main difference to Ignore is that the test are executed, but test failures are ignored.

If the test passes without an error, then it will be reported as failure since the PendingFeature annotation should be removed.

This way the tests will become part of the normal tests instead of being ignored forever.

Groovy has the groovy.transform.NotYetImplemented annotation which is similar but behaves a differently.

-

it will mark failing tests as passed

-

if at least one iteration of a data-driven test passes it will be reported as error

PendingFeature:

-

it will mark failing tests as skipped

-

if at least one iteration of a data-driven test fails it will be reported as skipped

-

if every iteration of a data-driven test passes it will be reported as error

@PendingFeature

def "not implemented yet"() { ... }PendingFeatureIf

To conditionally indicate that a feature is not fully implemented, and should not be reported as an error you can annotate

it as spock.lang.PendingFeatureIf and include a precondition similar to IgnoreIf or Requires

If the conditional expression passes it behaves the same way as PendingFeature, otherwise it does nothing.

For instance, annotating a feature as @PendingFeatureIf({ false }) effectively does nothing, but annotating it as

@PendingFeatureIf({ true }) behaves the same was as if it was marked as @PendingFeature

If applied to a data driven feature, the closure can also access the data variables. If the closure does not reference any actual data variables, the whole feature is deemed pending and only if all iterations become successful will be marked as failing. But if the closure actually does reference valid data variables, the individual iterations where the condition holds are deemed pending and each will individually fail as soon as it would be successful without this annotation.

@PendingFeatureIf({ os.windows })

def "I'm not yet implemented on windows, but I am on other operating systems"() {

@PendingFeatureIf({ sys.targetEnvironment == "prod" })

def "This feature isn't deployed out to production yet, and isn't expected to pass"() {It is also supported to have multiple @PendingFeatureIf annotations or a mixture of @PendingFeatureIf and

@PendingFeature, for example to ignore certain exceptions only under certain conditions.

@PendingFeature(exceptions = UnsupportedOperationException)

@PendingFeatureIf(

exceptions = IllegalArgumentException,

value = { os.windows },

reason = 'Does not yet work on Windows')

@PendingFeatureIf(

exceptions = IllegalAccessException,

value = { jvm.java8 },

reason = 'Does not yet work on Java 8')

def "I have various problems in certain situations"() {Stepwise

To execute features in the order that they are declared, annotate a spec class with spock.lang.Stepwise:

@Stepwise

class RunInOrderSpec extends Specification {

def "I run first"() { expect: true }

def "I run second"() { expect: false }

def "I will be skipped"() { expect: true }

}Stepwise only affects the class carrying the annotation; not sub or super classes. Features after the first

failure are skipped.

Stepwise does not override the behaviour of annotations such as Ignore, IgnoreRest, and IgnoreIf, so care

should be taken when ignoring feature methods in spec classes annotated with Stepwise.

|

Note

|

This will also set the execution mode to SAME_THREAD, see Parallel Execution for more information.

|

Since Spock 2.2, Stepwise can be applied to data-driven feature methods, having the effect of executing them sequentially (even if concurrent test mode is active) and to skip subsequent iterations if one iteration fails:

class SkipAfterFailingIterationSpec extends Specification {

@Stepwise

def "iteration #count"() {

expect:

count != 3

where:

count << (1..5)

}

}This will pass for the first two iterations, fail on the third and skip the remaining two. Without Stepwise on feature method level, the third iteration would fail and the remaining 4 iterations would pass.

|

Note

|

For backward compatibility with Spock versions prior to 2.2, applying the annotation on spec level will not automatically skip subsequent feature method iterations upon failure in a previous iteration. If you want that in addition to (or instead of) step-wise spec mode, you do have to annotate each individual feature method you wish to have that capability. This also conforms to the principle that if you want to skip tests under whatever conditions, you ought to document your intent explicitly. |

Timeout

To fail a feature method, fixture, or class that exceeds a given execution duration, use spock.lang.Timeout,

followed by a duration, and optionally a time unit. The default time unit is seconds.

When applied to a feature method, the timeout is per execution of one iteration, excluding time spent in fixture methods:

@Timeout(5)

def "I fail if I run for more than five seconds"() { ... }

@Timeout(value = 100, unit = TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS)

def "I better be quick" { ... }Applying Timeout to a spec class has the same effect as applying it to each feature that is not already annotated

with Timeout, excluding time spent in fixtures:

@Timeout(10)

class TimedSpec extends Specification {

def "I fail after ten seconds"() { ... }

def "Me too"() { ... }

@Timeout(value = 250, unit = MILLISECONDS)

def "I fail much faster"() { ... }

}When applied to a fixture method, the timeout is per execution of the fixture method.

When a timeout is reported to the user, the stack trace shown reflects the execution stack of the test framework when the timeout was exceeded. Additionally, thread dumps can be captured and logged on unsuccessful interrupt attempts if configured using the Spock Configuration File.

timeout {

// boolean, default false

printThreadDumpsOnInterruptAttempts true

// integer, default 3

maxInterruptAttemptsWithThreadDumps 1

// org.spockframework.runtime.extension.builtin.ThreadDumpUtilityType, default JCMD

threadDumpUtilityType ThreadDumpUtilityType.JSTACK

// list of java.lang.Runnable, default []

interruptAttemptListeners.add({ println('Unsuccessful interrupt occurred!') })

}Retry

The @Retry extensions can be used for flaky integration tests, where remote systems can fail sometimes.

By default it retries an iteration 3 times with 0 delay if either an Exception or AssertionError has been thrown, all this is configurable.

In addition, an optional condition closure can be used to determine if a feature should be retried.

It also provides special support for data driven features, offering to either retry all iterations or just the failing ones.

class FlakyIntegrationSpec extends Specification {

@Retry

def retry3Times() { ... }

@Retry(count = 5)

def retry5Times() { ... }

@Retry(exceptions=[IOException])

def onlyRetryIOException() { ... }

@Retry(condition = { failure.message.contains('foo') })

def onlyRetryIfConditionOnFailureHolds() { ... }

@Retry(condition = { instance.field != null })

def onlyRetryIfConditionOnInstanceHolds() { ... }

@Retry

def retryFailingIterations() {

...

where:

data << sql.select()

}

@Retry(mode = Retry.Mode.FEATURE)

def retryWholeFeature() {

...

where:

data << sql.select()

}

@Retry(delay = 1000)

def retryAfter1000MsDelay() { ... }

}Retries can also be applied to spec classes which has the same effect as applying it to each feature method that isn’t already annotated with {@code Retry}.

@Retry

class FlakyIntegrationSpec extends Specification {

def "will be retried with config from class"() {

...

}

@Retry(count = 5)

def "will be retried using its own config"() {

...

}

}A {@code @Retry} annotation that is declared on a spec class is applied to all features in all subclasses as well, unless a subclass declares its own annotation. If so, the retries defined in the subclass are applied to all feature methods declared in the subclass as well as inherited ones.

Given the following example, running FooIntegrationSpec will execute both inherited and foo with one retry.

Running BarIntegrationSpec will execute inherited and bar with two retries.

@Retry(count = 1)

abstract class AbstractIntegrationSpec extends Specification {

def inherited() {

...

}

}

class FooIntegrationSpec extends AbstractIntegrationSpec {

def foo() {

...

}

}

@Retry(count = 2)

class BarIntegrationSpec extends AbstractIntegrationSpec {

def bar() {

...

}

}Check RetryFeatureExtensionSpec for more examples.

Use

To activate one or more Groovy categories within the scope of a feature method or spec, use spock.util.mop.Use:

class ListExtensions {

static avg(List list) { list.sum() / list.size() }

}

class UseDocSpec extends Specification {

@Use(ListExtensions)

def "can use avg() method"() {

expect:

[1, 2, 3].avg() == 2

}

}This can be useful for stubbing of dynamic methods, which are usually provided by the runtime environment (e.g. Grails). It has no effect when applied to a helper method. However, when applied to a spec class, it will also affect its helper methods.

To use multiple categories, you can either give multiple categories to the value attribute

of the annotation or you can apply the annotation multiple times to the same target.

|

Note

|

This will also set the execution mode to SAME_THREAD if applied on a Specification, see Parallel Execution for more information.

|

ConfineMetaClassChanges

To confine meta class changes to the scope of a feature method or spec class, use spock.util.mop.ConfineMetaClassChanges:

@Stepwise

class ConfineMetaClassChangesDocSpec extends Specification {

@ConfineMetaClassChanges(String)

def "I run first"() {

when:

String.metaClass.someMethod = { delegate }

then:

String.metaClass.hasMetaMethod('someMethod')

}

def "I run second"() {

when:

"Foo".someMethod()

then:

thrown(MissingMethodException)

}

}When applied to a spec class, the meta classes are restored to the state that they were in before setupSpec was executed,

after cleanupSpec is executed.

When applied to a feature method, the meta classes are restored to as they were after setup was executed,

before cleanup is executed.

To confine meta class changes for multiple classes, you can either give multiple classes to the value attribute

of the annotation or you can apply the annotation multiple times to the same target.

|

Caution

|

Temporarily changing the meta classes is only safe when specs are run in a single thread per JVM. Even though many execution environments do limit themselves to one thread per JVM, keep in mind that Spock cannot enforce this. |

|

Note

|

This will acquire a READ_WRITE lock for Resources.META_CLASS_REGISTRY, see Parallel Execution for more information.

|

RestoreSystemProperties

Saves system properties before the annotated feature method (including any setup and cleanup methods) gets run, and restores them afterwards.

Applying this annotation to a spec class has the same effect as applying it to all its feature methods.

@RestoreSystemProperties

def "determines family based on os.name system property"() {

given:

System.setProperty('os.name', 'Windows 7')

expect:

OperatingSystem.current.family == OperatingSystem.Family.WINDOWS

}|

Caution

|

Temporarily changing the values of system properties is only safe when specs are run in a single thread per JVM. Even though many execution environments do limit themselves to one thread per JVM, keep in mind that Spock cannot enforce this. |

|

Note

|

This will acquire a READ_WRITE lock for Resources.SYSTEM_PROPERTIES, see Parallel Execution for more information.

|

AutoAttach

Automatically attaches a detached mock to the current specification.

@AutoAttach can only be used regular instance fields, not on shared or static ones.

Use this, if there is no direct framework support available.

To create detached mocks, see Create Mocks Outside Specifications

Spring and Guice dependency injection is automatically handled by the Spring Module and Guice Module, respectively.

AutoCleanup

Automatically clean up a field or property at the end of its lifetime by using spock.lang.AutoCleanup.

By default, an object is cleaned up by invoking its parameterless close() method. If some other

method should be called instead, override the annotation’s value attribute:

// invoke foo.dispose()

@AutoCleanup("dispose")

def fooIf multiple fields or properties are annotated with AutoCleanup, their objects are cleaned up sequentially, in reverse

field/property declaration order, starting from the most derived class class and walking up the inheritance chain.

If a cleanup operation fails with an exception, the exception is reported by default, and cleanup proceeds with the next

annotated object. To prevent cleanup exceptions from being reported, override the annotation’s quiet attribute:

@AutoCleanup(quiet = true)

def ignoreMyExceptionsTempDir

In order to generate a temporary directory for test and delete it after test, annotate a member field of type

java.io.File, java.nio.file.Path or untyped using def in a spec class (def will inject a Path).

Alternatively, you can annotate a field with a custom type that has a public constructor accepting either java.io.File or java.nio.file.Path as its single parameter (see FileSystemFixture for an example).

If the annotated field is @Shared, the temporary directory will be shared in the corresponding specification, otherwise every feature method and every iteration per parametrized feature method will have their own temporary directories.

Since Spock 2.4, you can also use parameter injection with @TempDir.

The types follow the same rules as for field injection.

Valid methods are setup(), setupSpec(), or any feature methods.

// all features will share the same temp directory path1

@TempDir

@Shared

Path path1

// all features and iterations will have their own path2

@TempDir

File path2

// will be injected using java.nio.file.Path

@TempDir

def path3

// use a custom class that accepts java.nio.file.Path as sole constructor parameter

@TempDir

FileSystemFixture path4

// Use for parameter injection of a setupSpec method

def setupSpec(@TempDir Path sharedPath) {

assert sharedPath instanceof Path

}

// Use for parameter injection of a setup method

def setup(@TempDir Path setupPath) {

assert setupPath instanceof Path

}

// Use for parameter injection of a feature

def demo(@TempDir Path path5) {

expect:

path1 instanceof Path

path2 instanceof File

path3 instanceof Path

path4 instanceof FileSystemFixture

path5 instanceof Path

}Cleanup

You can configure the cleanup behavior via @TempDir(cleanup = <mode>).

-

DEFAULTwill use the global value -

ALWAYSSpock will delete temporary directories after tests -

NEVERSpock will not delete temporary directories after tests. -

ON_SUCCESSSpock will not delete temporary directories if a test failed.

The global value for DEFAULT is taken from system property spock.tempdir.cleanup, or the configuration file.

If nothing is configured, it will default to ALWAYS.

Configuration

If you want to customize the parent directory for temporary directories, you can use the Spock Configuration File.

tempdir {

// java.nio.Path object, default null,

// which means system property "java.io.tmpdir"

baseDir Paths.get("/tmp")

// boolean, default is system property "spock.tempDir.keep"

keep true

// spock.lang.TempDir.CleanupMode, default ALWAYS

// allows to set the default cleanup mode to use

cleanup spock.lang.TempDir.CleanupMode.ON_SUCCESS

}Title and Narrative

To attach a natural-language name to a spec, use spock.lang.Title:

@Title("This is easy to read")

class ThisIsHarderToReadSpec extends Specification {

...

}Similarly, to attach a natural-language description to a spec, use spock.lang.Narrative:

@Narrative("""

As a user

I want foo

So that bar

""")

class GiveTheUserFooSpec() { ... }See

To link to one or more references to external information related to a specification or feature, use spock.lang.See:

@See("https://spockframework.org/spec")

class SeeDocSpec extends Specification {

@See(["https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levenshtein_distance", "https://www.levenshtein.net/"])

def "Even more information is available on the feature"() {

expect: true

}

@See("https://www.levenshtein.de/")

@See(["https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levenshtein_distance", "https://www.levenshtein.net/"])

def "And even more information is available on the feature"() {

expect: true

}

}Issue

To indicate that a feature or spec relates to one or more issues in an external tracking system, use spock.lang.Issue:

@Issue("https://my.issues.org/FOO-1")

class IssueDocSpec extends Specification {

@Issue("https://my.issues.org/FOO-2")

def "Foo should do bar"() {

expect: true

}

@Issue(["https://my.issues.org/FOO-3", "https://my.issues.org/FOO-4"])

def "I have two related issues"() {

expect: true

}

@Issue(["https://my.issues.org/FOO-5", "https://my.issues.org/FOO-6"])

@Issue("https://my.issues.org/FOO-7")

def "I have three related issues"() {

expect: true

}

}If you have a common prefix URL for all issues in a project, you can use the Spock Configuration File to set it up

for all at once. If it is set, it is prepended to the value of the @Issue annotation when building the URL.

If the issueNamePrefix is set, it is prepended to the value of the @Issue annotation when building the name for the

issue.

report {

issueNamePrefix 'Bug '

issueUrlPrefix 'https://my.issues.org/'

}Subject

To indicate one or more subjects of a spec, use spock.lang.Subject:

@Subject([Foo, Bar])

class SubjectDocSpec extends Specification {You can also use multiple @Subject annotations:

@Subject(Foo)

@Subject(Bar)

class SubjectDocSpec extends Specification {Additionally, Subject can be applied to fields and local variables:

@Subject

Foo myFooSubject currently has only informational purposes.

Rule

Spock understands @org.junit.Rule annotations on non-@Shared instance fields when the JUnit 4 module is included. The according rules are run at the

iteration interception point in the Spock lifecycle. This means that the rules before-actions are done before the

execution of setup methods and the after-actions are done after the execution of cleanup methods.

ClassRule

Spock understands @org.junit.ClassRule annotations on @Shared fields when the JUnit 4 module is included. The according rules are run at the

specification interception point in the Spock lifecycle. This means that the rules before-actions are done before the

execution of setupSpec methods and the after-actions are done after the execution of cleanupSpec methods.

Include and Exclude

Spock is capable of including and excluding specifications according to their classes, super-classes and interfaces and according to annotations that are applied to the specification.Spock is also capable of including and excluding individual features according to annotations that are applied to the feature method.The configuration for what to include or exclude is done according to the Spock Configuration File section.

import some.pkg.Fast

import some.pkg.IntegrationSpec

runner {

include Fast // could be either an annotation or a (base) class

exclude {

annotation some.pkg.Slow

baseClass IntegrationSpec

}

}Tags

Since version 2.2 Spock supports JUnit Platform tags. See the platform documentation for more information regarding valid tag values and how to configure your test execution to use them.

The @Tag annotation can be used to tag a spec or feature with one or more tags.

If applied on a spec, the tags are applied to all features in the spec.

Tags are inherited from parent specs.

If applied on a feature, the tags are applied to the feature.

@Tag("docs")

class TagDocSpec extends Specification {

def "has one tag"() {

expect: true

}

@Tag("other")

def "has two tags"() {

expect: true

}

}|

Note

|

JUnit Jupiter also has a @Tag annotation, but it will have no effect when used on a Specification.

|

Repeat until failure

Since version 2.3 the @RepeatUntilFailure annotation can be used to repeat a single feature until it fails or until it reaches the maxAttempts value.

This is intended to aid in manual debugging of flaky tests and should not be committed to source control.

Optimize Run Order

Spock can remember which features last failed and how often successively and also how long a feature needed to be

tested. For successive runs Spock will then first run features that failed at last run and first features that failed

more often successively. Within the previously failed or non-failed features Spock will run the fastest tests first.

This behaviour can be enabled according to the Spock Configuration File section. The default value is false.

runner {

optimizeRunOrder true

}Snapshot testing

Since version 2.4, the @Snapshot extension has been added for snapshot testing.

This type of testing compares the current output of your code with a saved version (a snapshot) to check for any changes.

It’s especially useful for checking if your code still produces the right text outputs after changes.

The @Snapshot extension also makes it easy to create and update these snapshots.

You use the @Snapshot extension along with the Snapshotter class.

The Snapshotter class provides the entrypoint for the tests.

You can use @Snapshot in two ways: you can add it to a field in your code, or you can use it as a parameter in a method.

The examples below will show you how to do both.

@Snapshot

Snapshotter snapshotter

def "using field based snapshot"() {

expect:

snapshotter.assertThat("from field").matchesSnapshot()

} def "using parameter based snapshot"(@Snapshot Snapshotter snapshotter) {

expect:

snapshotter.assertThat("from parameter").matchesSnapshot()

}You can store and assert over multiple snapshots by providing an optional snapshotId as identifier.

def "multi snapshot"() {

expect:

snapshotter.assertThat("from parameter").matchesSnapshot()

snapshotter.assertThat("other parameter").matchesSnapshot("otherId")

}By default, snapshots are stored and compared as plain text. However, you can plug your own matching logic. For example, you could compare two json structures with a third-party library.

def "custom matching"() {

expect:

snapshotter.assertThat("data").matchesSnapshot { snapshot, actual ->

/* Hamcrest matchers */

assertThat(actual, equalTo(snapshot))

}

}You can also extend from the Snapshotter class to provide your own convenience methods.

Check org.spockframework.specs.extension.SpockSnapshotter in the spock codebase for an example.

Configuration

The snapshots are stored in the rootPath directory, which can be configured either in the Spock Configuration File, or via the spock.snapshots.rootPath system property.

The rootPath directory is required and the @Snapshot extension will throw an exception if it is not configured when the extension is used.

Snapshots can be updated when setting the spock.snapshots.updateSnapshots system property to true, or via the config file.

You can configure the extension to store the actual value in case of a mismatch by setting the spock.snapshots.writeActual system property to true, or via the config file.

If enabled the extension will store the result in a file next to the original one with an additional .actual extension.

The .actual file will automatically be deleted on the next successful run, as long as the feature is still enabled.

This option is useful, when the snapshot is too large or complex to analyze with the built-in reporting.

snapshots {

rootPath = Paths.get("src/test/resources")

updateSnapshots = System.getenv("UPDATE_SNAPSHOTS") == "true"

writeActualSnapshotOnMismatch = !System.getenv("CI")

defaultExtension = 'snap.groovy'

}The @Snapshot extension will also set the snapshot tag on the affected features.

This can be utilized to only run the features that produce snapshots when updating them.

tasks.named("test", Test) {

useJUnitPlatform()

// set the snapshot directory, as resources are already an input we don't need to track them separately

systemProperty("spock.snapshots.rootPath", "src/test/resources")

// allow updating the snapshots with running `gradlew test -PupdateSnapshots`

if (project.hasProperty("updateSnapshots")) {

systemProperty("spock.snapshots.updateSnapshots", "true")

// not strictly necessary but speeds up the process by only executing snapshot tests

useJUnitPlatform {

includeTags("snapshot")

}

}

}Third-Party Extensions

You can find a list of third-party extensions in the Spock Wiki.

Writing Custom Extensions

There are two types of extensions that can be created for usage with Spock. These are global extensions and annotation driven local extensions. For both extension types you implement a specific interface which defines some callback methods. In your implementation of those methods you can set up the magic of your extension, for example by adding interceptors to various interception points that are described below.

It depends on your use case which type of annotation you create. If you want to do something once during the Spock run - at the start or end - or want to apply something to all executed specifications without the user of the extension having to do anything besides including your extension in the classpath, then you should opt for a global extension. If you instead want to apply your magic only by choice of the user, then you should implement an annotation driven local extension.

Global Extensions

To create a global extension you need to create a class that implements the interface IGlobalExtension and put its

fully-qualified class name in a file META-INF/services/org.spockframework.runtime.extension.IGlobalExtension in the

class path. As soon as these two conditions are satisfied, the extension is automatically loaded and used when Spock is

running.

IGlobalExtension has the following three methods:

start()-

This is called once at the very start of the Spock execution.

visitSpec(SpecInfo spec)-

This is called once for each specification. In this method you can prepare a specification with your extension magic, like attaching interceptors to various interception points as described in the chapter Interceptors.

stop()-

This is called at least once at the very end of the Spock execution.

Annotation Driven Local Extensions

To create an annotation driven local extension you need to create a class implementing the interface

IAnnotationDrivenExtension. As type argument to the interface you need to supply an annotation class having

@Retention set to RUNTIME, @Target set to one or more of FIELD, METHOD, and TYPE - depending on where you

want your annotation to be applicable - and @ExtensionAnnotation applied, with the IAnnotationDrivenExtension class

as argument. Of course the annotation class can have some attributes with which the user can further configure the

behaviour of the extension for each annotation application.

Your annotation can be applied to a specification, a feature method, a fixture method or a field. On all other places

like helper methods or other places if the @Target is set accordingly, the annotation will be ignored and has no

effect other than being visible in the source code, except you check its existence in other places yourself.

Since Spock 2.0 your annotation can also be defined as @Repeatable and applied multiple times to the same target.

IAnnotationDrivenExtension has visit…Annotations methods that are called by Spock with all annotations of the

extension applied to the same target. Their default implementations will then call the respective singular

visit…Annotation method once for each annotation. If you want a repeatable annotation that is compatible with

Spock before 2.0 you need to make the container annotation an extension annotation itself and handle all cases

accordingly, but you need to make sure to only handle the container annotation if Spock version is before 2.0,

or your annotations might be handled twice. Be aware that the repeatable annotation can be attached to the target

directly, inside the container annotation or even both if the user added the container annotation manually

and also attached one annotation directly.

Repeatable annotations are not supported for parameter annotations, as they are primarily intended to provide a value and only a singular value is allowed.

IAnnotationDrivenExtension has the following nine methods, where in each you can prepare a specification with your

extension magic, like attaching interceptors to various interception points as described in the chapter

Interceptors:

visitSpecAnnotations(List<T> annotations, SpecInfo spec)-

This is called once for each specification where the annotation is applied one or multiple times with the annotation instances as first parameter, and the specification info object as second parameter. The default implementation calls

visitSpecAnnotationonce for each given annotation. visitSpecAnnotation(T annotation, SpecInfo spec)-

This is used as singular delegate for

visitSpecAnnotationsand is otherwise not called by Spock directly. The default implementation throws an exception. visitFieldAnnotations(List<T> annotations, FieldInfo field)-

This is called once for each field where the annotation is applied one or multiple times with the annotation instances as first parameter, and the field info object as second parameter. The default implementation calls

visitFieldAnnotationonce for each given annotation. visitFieldAnnotation(T annotation, FieldInfo field)-

This is used as singular delegate for

visitFieldAnnotationsand is otherwise not called by Spock directly. The default implementation throws an exception. visitFixtureAnnotations(List<T> annotations, MethodInfo fixtureMethod)-

This is called once for each fixture method where the annotation is applied one or multiple times with the annotation instances as first parameter, and the fixture method info object as second parameter. The default implementation calls

visitFixtureAnnotationonce for each given annotation. visitFixtureAnnotation(T annotation, MethodInfo fixtureMethod)-

This is used as singular delegate for

visitFixtureAnnotationsand is otherwise not called by Spock directly. The default implementation throws an exception. visitFeatureAnnotations(List<T> annotations, FeatureInfo feature)-

This is called once for each feature method where the annotation is applied one or multiple times with the annotation instances as first parameter, and the feature info object as second parameter. The default implementation calls

visitFeatureAnnotationonce for each given annotation. visitFeatureAnnotation(T annotation, FeatureInfo feature)-

This is used as singular delegate for

visitFeatureAnnotationsand is otherwise not called by Spock directly. The default implementation throws an exception. visitParameterAnnotation(T annotation, ParameterInfo parameter)-

This is called once for each parameter of a feature or fixture method where the annotation is applied to. It gets the annotation instance as first parameter and the

ParameterInfoobject as second parameter. visitSpec(SpecInfo spec)-

This is called once for each specification within which the annotation is applied to at least one of the supported places like defined above. It gets the specification info object as sole parameter. This method is called after all other methods of this interface for each applied annotation are processed.

Configuration Objects

You can add own sections in the Spock Configuration File for your extension by creating POJOs or POGOs that are

annotated with @ConfigurationObject and have a default constructor (either implicitly or explicitly). The argument to

the annotation is the name of the top-level section that is added to the Spock configuration file syntax. The default

values for the configuration options are defined in the class by initializing the fields at declaration time or in the

constructor. In the Spock configuration file those values can then be edited by the user of your extension.

|

Note

|

It is an error to have multiple configuration objects with the same name, so choose wisely if you pick one and probably prefix it with some package-like name to minimize the risk for name clashes with other extensions or the core Spock code. |

To use the values of the configuration object in your extension, you can either use constructor injection or field injection.

-

To use constructor injection just define a constructor with one or more configuration object parameters.

-

To use field injection just define an uninitialized non-final instance field of that type.

Spock will then automatically create exactly one instance of the configuration object per Spock run, apply the

settings from the configuration file to it (before the start() methods of global extensions are called) and inject

that instance into the extension class instances.

|

Note

|

Constructor injection has a higher priority than field injection and Spock won’t inject any fields if it finds a suitable constructor. If you want to support both Spock 1.x and 2.x you can either use only field injection (Spock 1.x only supports field injection), or you can have both a default constructor and an injectable constructor, this way Spock 2.x will use constructor injection and Spock 1.x will use field injection. |

If a configuration object should be used exclusively in an annotation driven local extension you must register it in

META-INF/services/spock.config.ConfigurationObject.

This is similar to a global extension, put the fully-qualified class name of the annotated class on a new line in the file.

This will cause the configuration object to properly get initialized and populated with the settings from the configuration file.

However, if the configuration object is used in a global extension, you can also use it just fine in an annotation driven local

extension. If the configuration object is only used in an annotation driven local extension, you will get an exception

when then configuration object is to be injected into the extension, and you will also get an error when the

configuration file is evaluated, and it contains the section, as the configuration object is not properly registered yet.

Interceptors

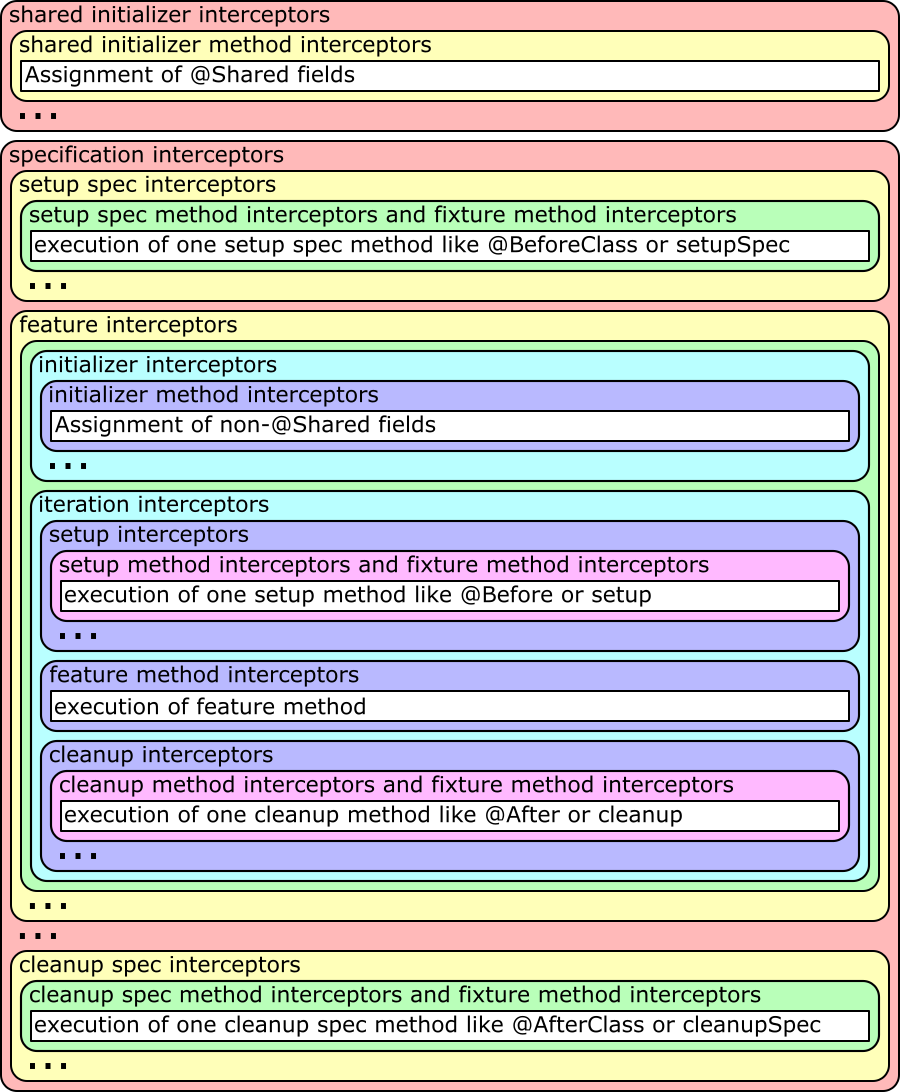

For applying the magic of your extension, there are various interception points, where you can attach interceptors from the extension methods described above to hook into the Spock lifecycle. For each interception point there can of course be multiple interceptors added by arbitrary Spock extensions (shipped or 3rd party). Their order currently depends on the order they are added, but there should not be made any order assumptions within one interception point.

An ellipsis in the figure means that the block before it can be repeated an arbitrary amount of times.

The … method interceptors are of course only run if there are actual methods of this type to be executed (the white

boxes) and those can inject parameters to be given to the method that will be run.

The shared initializer method interceptor and initializer method interceptor are called around two methods that are

generated by the compiler if there are @Shared, respectively non-@Shared, fields that get values assigned at

declaration time. The compiler will put those initializations in a generated method and call it at the proper place in

the lifecycle. So if there are no such initializations, no method is generated and thus the method interceptor is never

called. The non-method interceptors are always called at the proper place in the lifecycle to do work that has to be

done at that time. There can also be multiple such methods, if you for example have a super specification that itself

has fields with initialization expressions.

To create an interceptor to be attached to an interception point, you need to create a class that implements the

interface IMethodInterceptor. This interface has the sole method intercept(IMethodInvocation invocation). The

invocation parameter can be used to get and modify the current state of execution. Each interceptor must call the

method invocation.proceed(), which will go on in the lifecycle, except you really want to prevent further execution of

the nested elements like shown in the figure above. But this should be a very rare use case.

If you write an interceptor that can be used at different interception points and should do different work at different

interception points, there is also the convenience class AbstractMethodInterceptor, which you can extend and which

provides various methods for overriding that are called for the various interception points. Most of these methods have

a double meaning, like interceptSetupMethod which is called for the setup interceptor and the setup method

interceptor. If you attach your interceptor to both of them and need a differentiation, you can check for

invocation.method.reflection, which will be set in the method interceptor case and null otherwise, or you can check

invocation.method.name which behaves the same, or you can check for invocation.target == invocation.instance.

Alternatively, you can of course build two different interceptors or add a parameter to your interceptor and create

two instances, telling each at addition time whether it is attached to the method interceptor or the other one.

class I extends AbstractMethodInterceptor {

I(def s) {}

}// DISCLAIMER: The following shows all possible injection points that you could use

// depending on need and situation. You should normally not need to

// register a listener to all these places.

//

// Also, when building an annotation driven local extension, you should

// consider where you want the effects to be present, for example only

// for the features in the same class (specInfo.features), or for features

// in the same and superclasses (specInfo.allFeatures), or also for

// features in subclasses (specInfo.bottomSpec.allFeatures), and so on.

// on SpecInfo

specInfo.specsBottomToTop*.addSharedInitializerInterceptor new I('shared initializer')

specInfo.allSharedInitializerMethods*.addInterceptor new I('shared initializer method')

specInfo.addInterceptor new I('specification')

specInfo.specsBottomToTop*.addSetupSpecInterceptor new I('setup spec')

specInfo.allSetupSpecMethods*.addInterceptor new I('setup spec method')

specInfo.allFeatures*.addInterceptor new I('feature')

specInfo.specsBottomToTop*.addInitializerInterceptor new I('initializer')

specInfo.allInitializerMethods*.addInterceptor new I('initializer method')

specInfo.allFeatures*.addIterationInterceptor new I('iteration')

specInfo.specsBottomToTop*.addSetupInterceptor new I('setup')

specInfo.allSetupMethods*.addInterceptor new I('setup method')

specInfo.allFeatures*.featureMethod*.addInterceptor new I('feature method')

specInfo.specsBottomToTop*.addCleanupInterceptor new I('cleanup')

specInfo.allCleanupMethods*.addInterceptor new I('cleanup method')

specInfo.specsBottomToTop*.addCleanupSpecInterceptor new I('cleanup spec')

specInfo.allCleanupSpecMethods*.addInterceptor new I('cleanup spec method')

specInfo.allFixtureMethods*.addInterceptor new I('fixture method')

// on FeatureInfo (already included above, handling all features)

featureInfo.addInterceptor new I('feature')

featureInfo.addIterationInterceptor new I('iteration')

featureInfo.featureMethod.addInterceptor new I('feature method')

// since Spock 2.4 there are also feature-scoped interceptors that only apply for a single feature

// they will execute before the spec interceptors

featureInfo.addInitializerInterceptor new I('feature scoped initializer')

featureInfo.addSetupInterceptor new I('feature scoped setup')

featureInfo.addCleanupInterceptor new I('feature scoped cleanup')

// you can also perform a feature-scoped interception of spec methods

featureInfo.parent.allInitializerMethods.each { method ->

featureInfo.addScopedMethodInterceptor(method, new I('feature scoped initializer method'))

}

featureInfo.parent.allSetupMethods.each { method ->

featureInfo.addScopedMethodInterceptor(method, new I('feature scoped setup method'))

}

featureInfo.parent.allCleanupMethods.each { method ->

featureInfo.addScopedMethodInterceptor(method, new I('feature scoped cleanup method'))

}Injecting Method Parameters

Starting with Spock 2.4, it is possible to create IAnnotationDrivenExtension that target method parameters directly.

The extension annotation must use the @Target({ElementType.PARAMETER}) and the extension must implement IAnnotationDrivenExtension.visitParameterAnnotation(T annotation, ParameterInfo parameter).

In the visitParameterAnnotation you can then register a custom interceptor, or use the convenience ParameterResolver.Interceptor to handle the parameter injection.

Parameter injection is supported for fixture methods, such as setup and cleanup, as well as for feature methods.

ParameterIndex extension@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

@Target(ElementType.PARAMETER)

@ExtensionAnnotation(ParameterIndexExtension)

@interface ParameterIndex {}

class ParameterIndexExtension implements IAnnotationDrivenExtension<ParameterIndex> {

@Override

void visitParameterAnnotation(ParameterIndex annotation, ParameterInfo parameter) {

Class<?> type = parameter.reflection.type

if (!(type in [int, Integer])) {

throw new SpockExecutionException("Parameter must be a int/Integer but was ${type}")

}

parameter.parent.addInterceptor( // (1)

new ParameterResolver.Interceptor( // (2)

parameter, // (3)

{ parameter.index } // (4)

))

}

}-

Add the interceptor to the method, which is the

parentof theParameterInfo. -

The built-in

ParameterResolver.Interceptorwill handle the boilerplate part of parameter injection. -

Pass the

ParameterInfoto the interceptor, so the interceptor knows which parameter it is handling. -

This is a

Function<IMethodInvocation, Object>, which is called by theParameterResolver.Interceptorto resolve the parameter value. Here we just return the value of theParameterInfo’s `indexproperty, but you could also do some more complex logic here.

ParameterIndex extension def setup(@ParameterIndex int param1) {

assert param1 == 0

}

def "test"(@ParameterIndex int param1, @ParameterIndex Integer param2, @ParameterIndex int param3) {

expect:

param1 == 0

param2 == 1

param3 == 2

}For Spock versions prior to 2.4 or for advanced use cases

If your interceptor should support custom method parameters for wrapped methods, this can be done by modifying

invocation.arguments. Two use cases for this would be a mocking framework that can inject method parameters that are

annotated with a special annotation, or some test helper that injects objects of a specific type that are created and

prepared for usage automatically.

When called from at least Spock 2.0, the arguments array will always have the size of the method parameter count,

so you can directly set the arguments you want to set. You cannot change the size of the arguments array either.

All parameters that did not yet get any value injected, either from data variables or some extension, will have the

value MethodInfo.MISSING_ARGUMENT and if any of those remain, after all interceptors were run, an exception will be

thrown.

|

Note

|

When your extension might be used with a version before Spock 2.0, the Inject Method Parameters

|

|

Note

|

Pre Spock 2.0 only: When using data driven features (methods with a

Of course, you can also make your extension only inject a value if none is set already, as the for this simply check whether Data Driven Feature with Injected Parameter pre Spock 2.0

Data Driven Feature with Injected Parameter post Spock 2.0

|

Mock Maker Extensions

Spock creates mock objects via the IMockMaker interface.

When Spock is creating a mock, it will ask the available mock makers in order of priority,

if it can mock the requested type. Spock will use the first mock maker which is capable to mock the requested type.

The following mock makers are built-in, and are selected in this order:

-

java-proxy: Uses thejava.lang.reflect.ProxyAPI to create mocks of interfaces. -

byte-buddy: Uses Byte Buddy to create mock objects.-

Requires

net.bytebuddy:byte-buddy1.9+ on the class path.

-

-

cglib: Deprecated: Uses CGLIB to create mock objects.-

Requires

cglib:cglib-nodep3.2.0+ on the class path.

-

-

mockito: Uses Mockito to create mock objects.-

Can be configured to use additional Mockito feature like mock

Serializable -

Requires

org.mockito:mockito-core4.11+ on the class path.

-

| Capability | java-proxy |

byte-buddy |

cglib |

mockito |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Interface |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Class |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Additional Interfaces |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Explicit Constructor Arguments |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Final Class |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

Final Method |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

Static Method |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

The class spock.mock.MockMakers provides constants and methods for the built-in mock makers.

You can select your preferred mock maker, by defining the preferredMockMaker property

in the Spock Configuration File.

The preferred mock maker will be used globally, if no mock maker is explicitly specified for a given mock.

mockMaker {

preferredMockMaker spock.mock.MockMakers.byteBuddy

}Mockito Mock Maker

The mockito Mock Maker provides the ability to mock final types, enums and final methods.

The mocking of final classes is automatically enabled, if org.mockito:mockito-core 4.11+ is on the class path.

For mocking of final methods, you need to select the mockito mock maker during mock construction,

like:

Subscriber subscriber = Mock(mockMaker: MockMakers.mockito)If you want to make final methods mockable by default, you can select this mock maker as the preferred mock maker. It can’t mock native methods, see the Mockito documentation for details.

|

Caution

|

If you try to mock a final method without a Mock Maker supporting it, it will silently fail, without honoring your specified interactions. |

You can configure the created mock objects using the interface org.mockito.MockSettings during the construction to use features provided by Mockito:

Subscriber subscriber = Mock(mockMaker: MockMakers.mockito {

serializable()

})The mockito mock maker uses org.mockito.MockMakers.INLINE under the hood,

please see the Mockito manual "Mocking final types, enums and final methods" for all pros and cons,

when using org.mockito.MockMakers.INLINE.

It also supports mocking of static methods of classes and interfaces with Mock/Stub/SpyStatic.

See static mocks section for more details.

Custom Mock Maker

Spock provides an extension point to plug in your own mock maker for creating mock objects.

To create a mock maker you need to create a class that implements the interface IMockMaker and put its

fully-qualified class name in a file META-INF/services/org.spockframework.mock.runtime.IMockMaker in the

class path. As soon as these two conditions are satisfied, your mock maker is automatically loaded and used when Spock is

running.

You should provide a constant class containing the mock maker ID or a method for creating IMockMakerSettings to your users,

that your mock maker can be easily selected.

The IMockMakerSettings can be used by a custom IMockMaker to provide mock maker specific API settings in a type-safe way.

The custom mock maker may subclass IMockMakerSettings to transport custom data from the declaration site to the mock

creation. The custom mock maker then provides a static method to create an instance of that subclass and the parameters

are then used during mock creation.

public final class FancyMockMaker implements IMockMaker {

static final MockMakerId ID = new MockMakerId("fancy");

private static final Set<MockMakerCapability> CAPABILITIES = EnumSet.of(

MockMakerCapability.CLASS,

MockMakerCapability.EXPLICIT_CONSTRUCTOR_ARGUMENTS);

public FancyMockMaker() {

}

@Override

public MockMakerId getId() {

return ID;

}

@Override

public Set<MockMakerCapability> getCapabilities() {

return CAPABILITIES;

}

@Override

public int getPriority() {

return 5000;

}

@Override

public Object makeMock(IMockCreationSettings settings) {

FancyMockMakerSettings fancySettings = settings.getMockMakerSettings();

return makeMockInternal(fancySettings);

}

@Override

public IMockabilityResult getMockability(IMockCreationSettings settings) {

FancyMockMakerSettings fancySettings = settings.getMockMakerSettings();

if (fancySettings != null &&

fancySettings.isSerialization() &&

!fancySettings.getFancyTypes().isEmpty()) {

return () -> "Mock with serialization and fancy types is not supported.";

}

return IMockabilityResult.MOCKABLE;

}

Object makeMockInternal(FancyMockMakerSettings settings) {

//Implementation omitted ...

return null;

}

}

final class FancyMockMakerSettings implements IMockMakerSettings {

private boolean serialization;

private final List<Type> specialTypes = new ArrayList<>();

FancyMockMakerSettings() {

}

boolean isSerialization() {

return serialization;

}

List<Type> getFancyTypes() {

return specialTypes;

}

@Override

public MockMakerId getMockMakerId() {

return FancyMockMaker.ID;

}

public void withSerialization() {

serialization = true;

}

public void fancyTypes(Type... types) {

this.specialTypes.addAll(Arrays.asList(types));

}

}

final class FancyMockMakers {

/**

* Public static entry point for the User.

*/

public static IMockMakerSettings fancyMock(

@DelegatesTo(FancyMockMakerSettings.class)

Closure<?> code) {

FancyMockMakerSettings settings = new FancyMockMakerSettings();

code.setDelegate(settings);

code.call();

return settings;

}

}when:

Mock(ArrayList, mockMaker: FancyMockMakers.fancyMock {

fancyTypes(List.class, String.class)

withSerialization()

})

then:

CannotCreateMockException ex = thrown()

ex.message == "Cannot create mock for class java.util.ArrayList. fancy: Mock with serialization and fancy types is not supported."Keeping State in Extensions

Prior to Spock 2.4, extensions could only store state either in their own instances or their interceptor instances.

Often, the state can be kept locally in the intercept(IMethodInvocation) method around the IMethodInvocation.proceed() call. However, there are cases where this is not possible, for example when using initializer interceptors.

Spock 2.4 adds a new org.spockframework.runtime.extension.IStore interface that allows extensions to store and retrieve data during the execution of a specification.

The store is available from the org.spockframework.runtime.extension.IMethodInvocation interface via the getStore(IStore.Namespace namespace) method. Currently, it is not possible to access the store directly from an extension, only via registering an interceptor.

The stores are hierarchical and follow roughly the same hierarchy as shown in the Spock Interceptors figure. The hierarchy is as follows:

Root

┗ Specification

┗ Feature

┗ IterationIf an item is not found in the current store, its parent store is searched, and so on until the root store is reached. For more information see the JavaDoc of org.spockframework.runtime.extension.IStore.

If an interceptor adds a Macguffin to the store via a sharedInitializerInterceptor for ASpec it will be available to all features (AFeature1 and AFeature2) and iterations (AFeature1[1], AFeature1[2], AFeature2[1], AFeature2[2]) of that specification, but not to BSpec or its features. Conversely, if a feature interceptor adds a Thingmajig to the store for AFeature1 it will be available to all its iterations (AFeature1[1], AFeature1[2]), but not to sibling features (AFeature2) or to the specification (ASpec).

|

Note

|

When the store is closed, it will call the close() method for all stored values that implement java.lang.AutoCloseable.

Stored values will be closed in reverse insertion order.

This does not happen, if the value was added and subsequently removed from the store, before the store was closed.

|

Example of a global extension using the Store

class ExceptionCounterGlobalExtension implements IGlobalExtension {

private static final Namespace EXAMPLE_NS = Namespace.create(ExceptionCounterGlobalExtension) // (1)

private static final String ACCUMULATOR = "accumulator"

private static final IMethodInterceptor INTERCEPTOR = {

try {

it.proceed()

} catch (Exception e) {

it.getStore(EXAMPLE_NS) // (6)

.get(ACCUMULATOR, ConcurrentHashMap) // (7)

.computeIfAbsent(e.class.name, { __ -> new AtomicInteger() }) // (8)

.incrementAndGet()

throw e

}

}

@Override

void visitSpec(SpecInfo spec) {

spec.allFeatures.featureMethod*.addInterceptor(INTERCEPTOR) // (2)

}

@Override

void executionStart(ISpockExecution spockExecution) { // (3)

spockExecution.getStore(EXAMPLE_NS) // (4)

.put(ACCUMULATOR, new ConcurrentHashMap()) // (5)

}

@Override

void executionStop(ISpockExecution spockExecution) { // (9)

def results = spockExecution.getStore(EXAMPLE_NS) // (10)

.get(ACCUMULATOR, ConcurrentHashMap)

if (!results.isEmpty()) {

println "========================"

println "==Exception statistics=="

println "========================"

results.toSorted().each { exceptionName, counter ->

println "${counter}x $exceptionName"

}

println "========================"

}

}

}-

The

Namespacefor the extension is created, here we use the extension’s class as key -

The extension registers the

INTERCEPTORfor each feature method -

executionStartis called right before the specifications are executed, it also gives access to the root-levelIStore -

The extensions uses its

Namespaceto retrieve theIStore -

It then puts a

ConcurrentHashMapinto the store to serve as collector for the data -

During the feature method execution the

INTERCEPTORretrieves theIStorevia the sharedNamespace -

It then retrieves the

ConcurrentHashMapvia the key, retrieval request will propagate through the hierarchy until it finds the value at the root-level -

It then increments the counter for the occurred exception type, creating the counter if it was not yet present.

-

executionStopis called after all tests have been executed and also give access to the root-levelIStore. The extension uses this to print a report of the collected exception statistics.

class ASpec extends Specification {

def "a failing test"() {

expect: false

}

def "a test failing with an exception"() {

given:

if(1==1) throw new IllegalStateException()

expect: true

}

}

class BSpec extends Specification {

def "illegal parameter for List"() {

given:

def value = new ArrayList<>(-1)

expect:

value.empty

}

def "illegal parameter for Map"() {

given:

def value = new HashMap(-1)

expect:

value.empty

}

}The extension generates the following output for the example code above.

========================

==Exception statistics==

========================

1x java.lang.IllegalStateException

2x java.lang.IllegalArgumentException

========================